By John Mauldin

Back in the 1980s and 1990s, many people thought excessive government spending and the resulting debt would bring inflation or even hyperinflation.

We wanted a hawkish Federal Reserve or, better yet, a gold standard to prevent it. Reality turned out differently.

Federal debt rose steadily, inflation didn’t. Here’s a chart of the on-budget public debt since 1970:

Source: St. Louis Fed

Here is the same data in terms of debt to GDP:

You can see the debt growth started to level out in the late 1990s but then took off again. Yet the only serious inflation in this whole period occurred in the first decade.

I am not saying we had no inflation at all. Obviously we did—and in many parts of the economy more than the CPI reflects.

Some of it showed up in asset prices (stocks, real estate) instead of consumer goods. We like that and typically don’t consider it inflation, but it is.

But there was nothing remotely like the kind of major inflation that this level of government debt should have caused.

My good friend Lacy Hunt of Hoisington Investment Management presented two important theorems that explain this phenomenon.

Debt Leads to Lower Interest Rates

I’ll start with a quote from Lacy:

Federal debt accelerations ultimately lead to lower, not higher, interest rates. Debt-funded traditional fiscal stimulus is extremely fleeting when debt levels are already inordinately high. Thus, additional and large deficits provide only transitory gains in economic activity, which are quickly followed by weaker business conditions. With slower economic growth and inflation, long-term rates inevitably fall.

The first sentence will shock many people who think rising federal debt raises interest rates through a “crowding out” effect.

That means the government—because it is the most creditworthy borrower—sucks up capital and leaves less available to private borrowers. They must then pay more for it via higher interest rates or a weakened currency.

That is the case for most countries in the world.

Yet clearly it has not been the case for larger developed economies. That’s not to say it never will be. But today’s situation supports Lacy’s point, and not just in the US.

In the US, Japan, the eurozone, and the UK, sovereign rates fell as government debt rose. That is not how most macroeconomic theories say debt-funded fiscal stimulus should work.

Additional cash flowing through the economy is supposed to spur growth and in turn raise inflation and interest rates. This has not happened.

The reason it hasn’t happened is that we have crossed a kind of debt Rubicon in recent history.

In much of the developed world, the existing debt load is so heavy that additional dollars have a smaller effect.The new debt’s negative effects outweigh any benefit.

The higher taxes that politicians often think will reduce the deficit serve mainly to depress business activity. The result is slower economic growth, plus lower interest rates and inflation.

Past performance is really not an indicator of future results.

Falling Money Velocity Makes Debt Unproductive

Lacy’s second theorem supports the first.

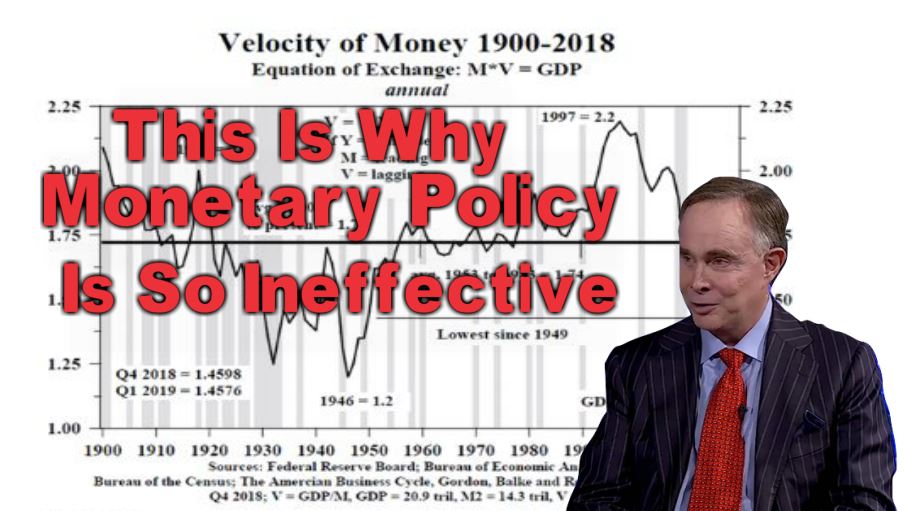

Monetary decelerations eventually lead to lower, not higher, interest rates as originally theorized by economist Milton Friedman. As debt productivity falls, the velocity of money declines, making monetary policy increasingly asymmetric (one sided) and ineffectual as a policy instrument.

The Federal Reserve controls money supply, but has no effect on its velocity. That is a serious problem.

Looser financial conditions don’t help when the economy has no productive uses for the new liquidity. With most industries already having enough capacity, the money had nowhere to go but back into the banks.

That’s why velocity fell 33% in the two decades that ended in 2018:

Now, if velocity is falling, then any kind of Fed stimulus faces a tough headwind. It can inject liquidity but can’t make people spend it, nor can it force banks to lend.

And in a fractional reserve system, money creation doesn’t go far unless the banks cooperate.

Conventional Stimulus Doesn’t Work Anymore

The banks respond to each crisis the same way.

And every time they find that it takes more aggressive action to produce the same effect. Obviously, that can’t go on forever.

In a world of falling monetary velocity, the amount of GDP growth produced by each additional dollar of debt fell 24% in the last 20 years.

The result is that public and private debt keeps rising but also becomes less productive. That’s why we have so much more debt now and yet slower growth.

This also explains why growth has been so sluggish since 2014. That was when money supply peaked. So for five years now, we’ve had both a shrinking money supply and slowing velocity.

That’s not a recipe for inflation. And the more recent jump in federal deficit spending is making matters worse, not better.

The Great Reset: The Collapse of the Biggest Bubble in History

New York Times best seller and renowned financial expert John Mauldin predicts an unprecedented financial crisis that could be triggered in the next five years. Most investors seem completely unaware of the relentless pressure that’s building right now. Learn more here.

0 Comments