First it was Baoshang Bank , then it was Bank of Jinzhou, then, two months ago, China’s Heng Feng Bank with 1.4 trillion yuan in assets, quietly failed and was just as quietly nationalized.

Today, a fourth prominent Chinese bank was on the verge of collapse under the weight of its bad loans, only this time the failure was far less quiet, as depositors of the rural lender swarmed the bank’s outlets in public, demanding their money in an angry demonstration of what Beijing is terrified of the most: a bank run.

Local business leaders, political cadres and banking executives rallied Thursday at the main branch of Henan Yichuan Rural Commercial Bank, just outside the central Chinese city of Luoyang, where they stood one by one before a microphone to pledge their backing for the bank, as smiling employees brandished wads of cash before television cameras to demonstrate just how much cash, literally, the bank had.

It was China’s latest, and most desperate attempt yet to project stability and reassure the public that all is well after rumors spread that the bank’s chairman was in trouble and the bank was on the brink of insolvency. However, as the WSJ reports, it wasn’t enough for 31-year-old Li Xue, who showed up for the third day Thursday to withdraw thousands of yuan of her mother’s life savings after hearing from fellow villagers that Yichuan Bank – which is the largest lender in Yichuan county by the number of branches and capital, and it is also a member of PBOC’s deposit insurance system, according to the local government – was going under.

Just like any self-respecting Ponzi scheme, the bank’s branch managers tried to persuade her to keep her money with them until March, when her mother’s three-year deposits would mature, yielding more than 10,000 yuan in interest. And then, just like any Ponzi scheme, to sweeten the offer, the bank managers also offered her even higher-yielding products, plus supermarket gift cards, just to keep her money there..

“Our bank is state-backed, and your money is insured by deposit insurance,” one female manager told her, but Ms. Li refused, her confidence in the state’s lies crushed.

“We really can’t afford to lose the money,” she said.

The bank run at Yichuan Bank, located in China’s landlocked province of Henan, makes it at least the fourth bank that authorities have rushed to rescue this year. It won’t be the last.

what’s on your mind.

As we have documented previously, in recent month China’s banking sector has been dogged by a sudden surge in liquidity concerns, particularly among smaller regional banks that had expanded aggressively in recent years, and were now suffering a surge in bad loans, threatening their viability.

In May, regulators bailed out Baoshang Bank, in the country’s first bank bailout since the 1990s. That move led to widespread concerns about the health of other small lenders and financial institutions, squeezing liquidity in China’s interbank market. It also led to similar failures – and rescues – of Bank of Jinzhou and Heng Feng Bank, both smallish regional banks, yet big enough to convince the local population that something was very rotten with China’s financial system.

Prudently, Beijing has been careful not to announce any takeovers, although it has quietly brought in state-owned banks and asset management firms, as well as an arm of the nation’s sovereign-wealth fund, to inject fresh capital and stabilize wobbly banks, as it did most recently in the case of Heng Feng.

Try as Beijing might, however, the bailouts have not gone unnoticed, and culminated in what today has been a three-day bank run at Yichuan Bank.

Like with everything else in China, there is good and bad news.

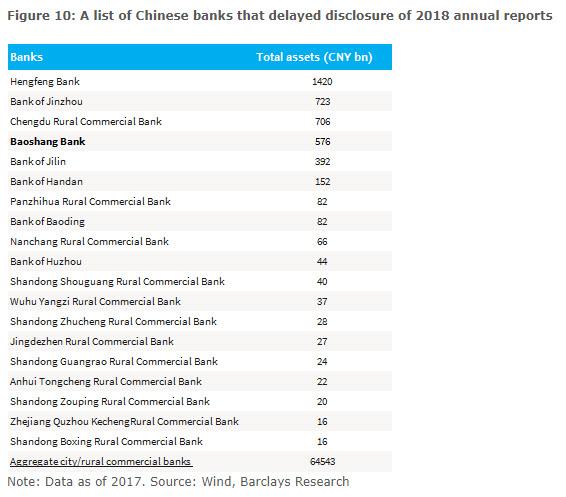

The good news is that troubled banks accounted for just 4% of total assets in China’s banking system, according to a recent estimate by S&P Global that included poor quality rural institutions flagged by the Chinese central bank. An analysis by Barclays listed those banks that had delayed to disclose their 2018 annual reports: a clear indicator of imminent collapse. Three of the top four banks have already been nationalized or bailed out.

However, in this case size really does not matter, and the aggressive response from regulators to the developments at Yichuan Bank, a small lender with just 62.65 billion yuan ($8.9 billion) in assets, underscores the heightened concerns of contagion and social instability amid the loss of confidence in bank deposits, as the WSJ notes.

The bad news is that small banks are just the start of a wave that could eventually topple some of China’s biggest SOEs. Yichuan Bank is emblematic of the thousands of banks and cooperatives in China’s countryside that in recent years had scaled up its ambitions. In 2009, the rural cooperative became a commercial lender, attracting deposits primarily from farmers and county locals, according to the bank. It then kept growing at a tremendous pace, raking up billions in bad loans, until one day – like all Ponzi schemes – the new money stopped trickling in and the bank’s day of reckoning had arrived.

While Yichuan Bank has plenty of competition, including large state-owned banks in nearby Luoyang, an ancient capital of China known, Yichuan Bank accounted for 71% of deposits and 82% of loans in its county as of September 2018, according to China Chengxin International Rating Agency.

The problem, as hinted above, is that like most other small Chinese banks, Yichuan Bank suffered from a buildup of bad loans as the economy slowed in recent years, and struggled to retain deposits amid intensified competition from its peers.

That was the proverbial Minsky moment when every Ponzi scheme ends.

Then the warnings came: in July, analysts at China Chengxin flagged the bank for its lack of stable deposits and a rapid buildup of overdue and bad loans. Bad loans ballooned to 1 billion yuan at the end of 2018, a 10-fold increase in just three years, according to its financial statements. Overdue loans, meantime, grew to 28% of its total credit at the end of September 2018, the credit rating agency said.

That number, incidentally, is orders of magnitude higher than what the PBOC discloses as China’s average bad loan percentage, which in the past decade has stubbornly, and erroneously, been stuck in the mid-1% range. The true number is far, far higher, but Beijing guards it with its life, as the alternative is a bank run on the world’s largest bank system, which with $40 trillion in assets, is roughly double that of the US.

So far Beijing has been lucky, in that people tend to be notoriously bad with numbers. Ironically, what brought the bank down was news of trouble with Yichuan’s senior management that initially caught locals’ attention. Immediately thereafter, depositors started demanding their money back earlier this month; as speculation circulated on social media that the bank was on the verge of insolvency, the crowds at bank branches grew thicker, and so the bank run began.

By Wednesday, the problem – and its media coverage – was too big to avoid, and local authorities moved swiftly to stabilize the situation. In typical Chinese fashion, however, instead of fixing the underlying problem, they blamed the messenger and announced they had detained two women whom they accused of spreading false rumors; they also brought in the county’s deputy party secretary to take charge.

And since explaining to the people that China’s entire financial system is one giant house of cards, the authorities needed a scapegoat. They got it when they announced an investigation into the bank’s former chairman, citing a violation of discipline, a charge commonly used in corruption cases.

Meanwhile, having received a few truckloads full of cash, county authorities tried to ease depositor panic saying they had tens of billions of yuan in funds available, which the bank had already begun tapping, according to the bank.

So far this approach has failed to restore confidence, and bank officers, overwhelmed with withdrawal requests, put stacks of cash on display behind bank windows. They dangled various inducements, “including boxes of tissue, plastic chairs, tea thermoses and loose leaf tea” according to the WSJ, to persuade customers to keep their deposits with Yichuan.

And why not: cheap bribes almost worked in Spain in 2012, when the then-insolvent Bankia handed out Spiderman towels in exchange for a €300 deposit.

Surprisingly, it did not work in China, as people continued to show up, adamant about withdrawing their funds; the bank run was accelerating, and nothing officials did could halt, or reverse it.

Zhang Yanting, a 51-year-old farmer, decided after several days of trying to pull his money out of the bank that he would keep his account open to collect the few dollars in grain subsidies he receives each year from the government. But Zhang still wanted most of his 13,000 yuan in deposits back.

After hours in line Thursday, the bank cashier handed him a wad of cash, which he happily stuffed into his bag. Zhang was unmoved by the promise of gifts, save for a bottle of water that he sipped from while waiting.

“I’ve been with the bank for 10 years and have never seen service this good,” he said.

Zhang was a happy customer: he learned that when dealing with a collapsing Ponzi scheme, only those who pull their money first stand to recover anything. It’s those who foolishly believed the government that will be far, far angrier when they realize that it’s gone… it’s all gone.

Article posted on ZeroHedge.com

0 Comments