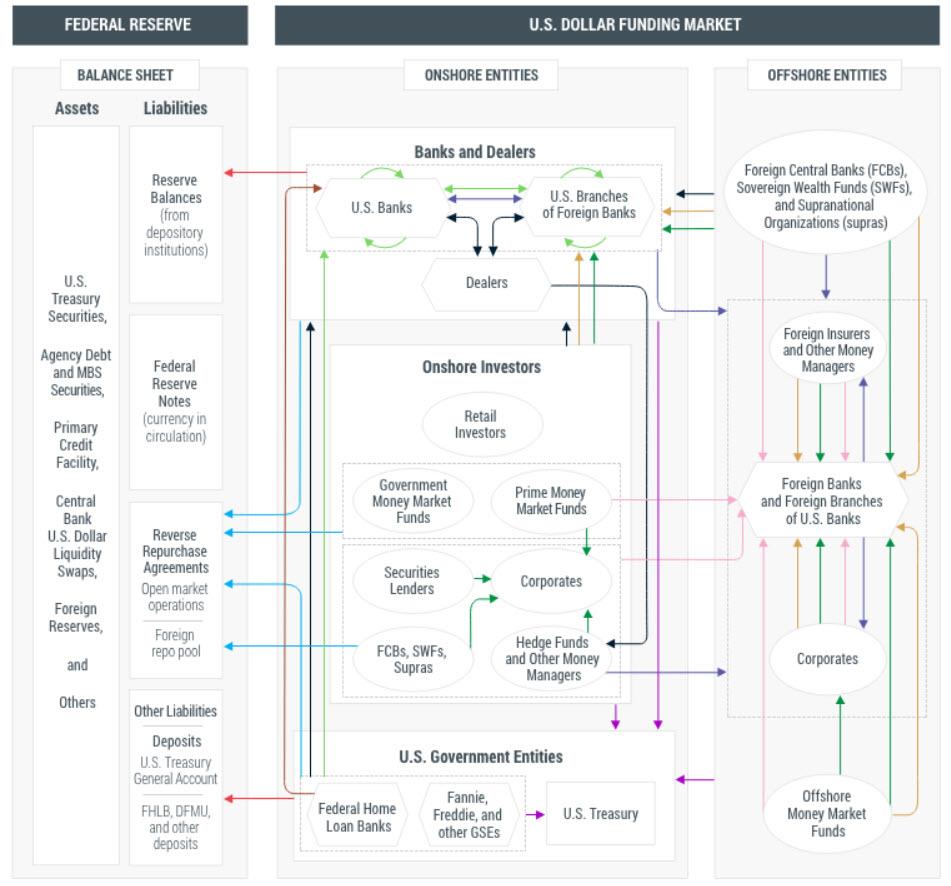

For the past decade, the name of Zoltan Pozsar has been among the most admired and respected on Wall Street: not only did the Hungarian lay the groundwork for our current understanding of the deposit-free shadow banking system – which has the often opaque and painfully complex short-term dollar funding and repo markets – at its core…

… but he was also instrumental during his tenure at both the US Treasury and the New York Fed in laying the foundations of the modern repo market, orchestrating the response to the global financial crisis and the ensuing policy debate (as virtually nobody at the Fed knew more about repo at the time than Pozsar), serving as point person on market developments for Fed, Treasury and White House officials throughout the crisis (yes, Kashkari was just the figurehead); playing the key role in building the TALF to backstop the ABS market, and advising the former head of the Fed’s Markets Desk, Brian Sack, on just how the NY Fed should implement its various market interventions without disrupting and breaking the most important market of all: the multi-trillion repo market.

In short, when Pozsar speaks (or as the case may be, writes), people listen (and read).

And since Pozsar moved from the public sector to Credit Suisse in February 2015 to write his market moving (at least for those who can understand it) periodical, “Global Money Notes”, it has been relatively easy to keep track of his thoughts and observations on the repo market as they change over time.

Which brings us to his latest Global Money Notes, #26, published overnight, and in which Pozsar delivers his scathing assessment of the Fed’s latest intervention to stabilize repo markets since the September 16 repocalypse, that sent overnight repo rates as high as 10% in what was previously seen as an impossible event. Of course, as we saw three months ago, not only was the event possible, but it led to a shockwave of confusion as to what caused it, prompting even the BIS to chime in over the weekend with a fascinating theory, discussed previously, that hedge funds were among the causes for the repo fireworks as they scrambled to procure funding to prevent their massively levered relative value trades in which they bought TSYs and sold ‘equivalent’ derivatives contracts, from collapsing.

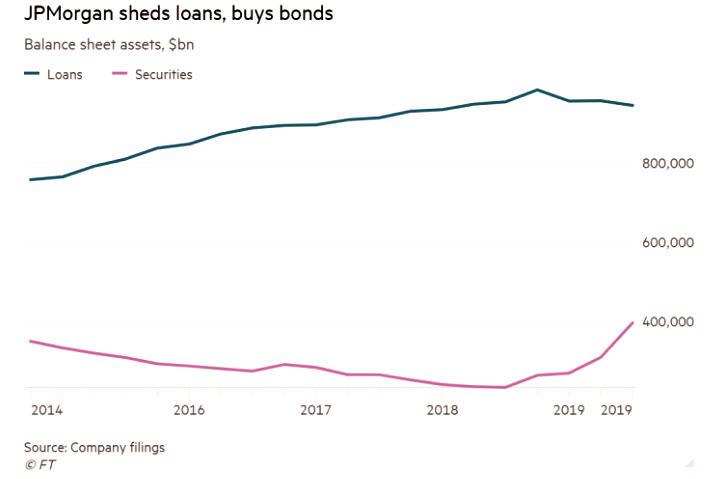

While Pozsar does not focus as much on the causes of the repocalypse, having previously covered them in depth in his prior Money Notes (and he would know: as noted above, Pozsar is the de facto architect of the modern US repo system), what he does do in his latest note, titled ominously “Countdown to QE4” is explain why the Fed’s interventions to date have failed to reverse the underlying plumbing issues in the banking system, manifesting themselves in a dramatic increase in Treasurys at the biggest US bank, JPMorgan…

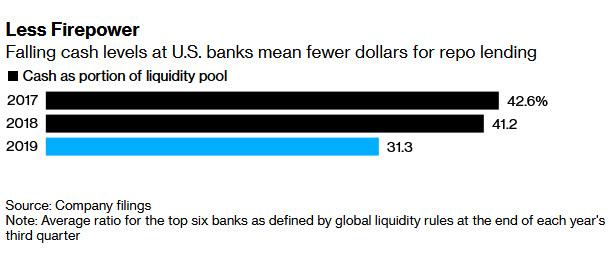

… offset by a decline in reserves, i.e. cash…

… at the largest US banks, something we addressed previously when we discussed how JPMorgan gamed the financial system to trigger “NOT QE”, and a topic that Bloomberg touches on overnight in “Repo Firepower Reduced by Falling Cash Levels at Big U.S. Banks.”

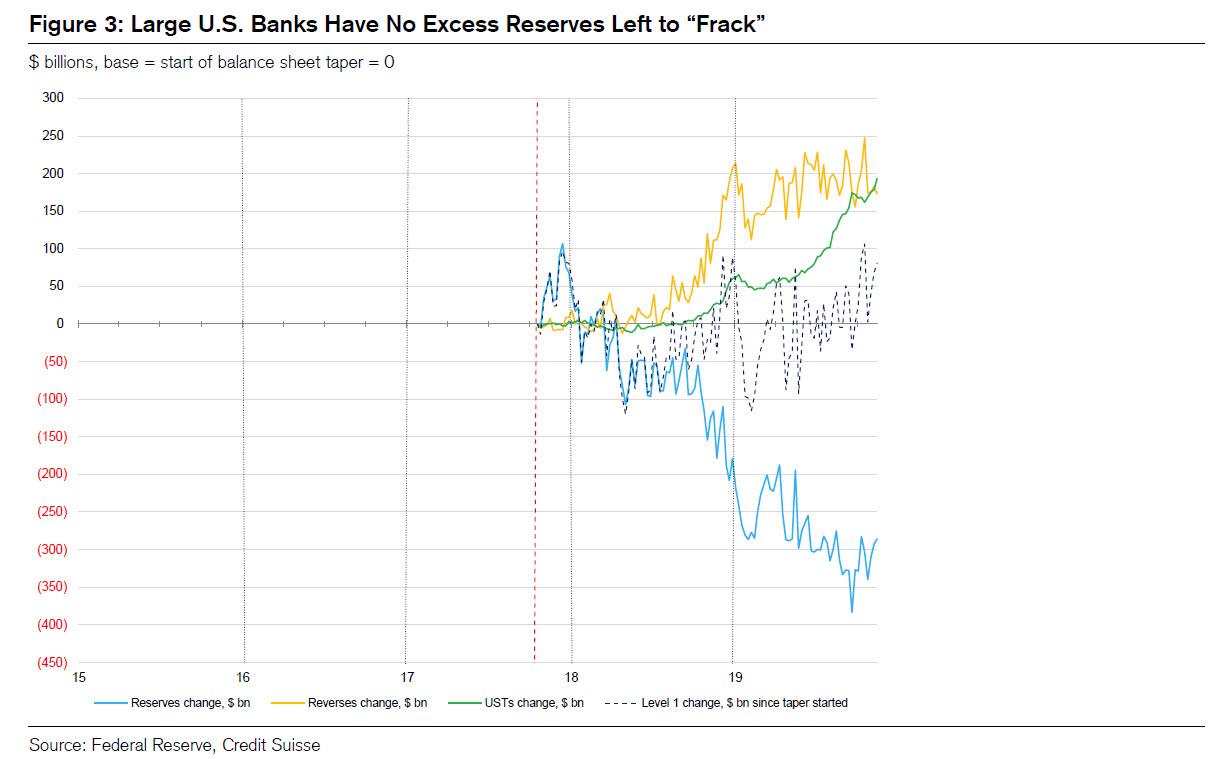

As Pozsar cautions, the core problem at the heart of the repo blockage is that as banks shifted from owning reserves to collateral (mostly Treasuries), for reasons we will address shortly, large U.S. banks like J.P. Morgan that are central to year-end flows spent some $350 billion of excess reserves on collateral since the beginning of the Fed’s balance sheet taper, leaving banks (and especially JPMorgan) dangerously low on reserves.

And while one can debate why banks shifted away from reserves to “collateral”, Pozsar has a simple theory: “dealers and banks loaded up on collateral as a trade – a trade they were supposed to be taken out of by eventual coupon purchases by the Fed.” In other words, here is a former Fed official admitting that banks were purchasing Treasuries as nothing more than a QE frontrunning ploy, something which the Fed has previously sworn was never the intention behind QE. After all, if it emerges that the Fed is essentially facilitating taxpayer-funded and perfectly legal frontrunning, making bank execs even richer in the process, the US central bank would have even fewer fans. And yet, here is arguably the most respected ex-Fed staffer explaining that one of the core roles of QE is just that.

Alas, here a problem emerged, because “the Fed never did that, and for the first time we’re heading into a year-end turn without any excess reserves.”

Indeed, instead of buying coupon bonds as Dealers have been quietly demanding behind close doors, a process which would allow them to sterilize their massive Treasury holdings, the Fed announced in October it would only buy T-Bills in order to not freak out the market that it is officially launching QE 4 (as a reminder, the only semantic distinction between whether the Fed is doing QE or not doing QE is whether it is soaking up duration; the Fed’s argument is that since Bills don’t have duration, it’s not QE. However once Powell starts buying 2Y, 3Y, 5Y and so on Treasuriess, the facade cracks and the Fed will have no more defense that what it is doing is precisely QE 4). And by buying Bills, it is not allowing commercial banks to exchange their coupon holdings for reserves (cash), but merely results in recirculation of sterilized Bill purchases.

Now most people don’t understand this, and instead repeat the old maxim “don’t fight the Fed” which they claim is adding liquidity through repos and bill purchases, and what’s not in the system now will be there on year-end, and the turn will be just fine.

Only as Pozsar says “Not so fast!” and explains:

What we need for the [year-end] turn to go well are balance sheet neutral repo operations, or asset purchases aimed at what dealers bought all year: coupons, not bills – the former to get around foreign banks’ balance sheet constraints around year-end, and the latter to ensure that excess reserves accumulate with large banks like J.P. Morgan. Unfortunately, the Fed is doing neither.

He goes on:

Repo operations are done through the tri-party system which means they aren’t nettable, which in turn means that once balance sheet constraints start to bind around year-end, foreign dealers will take less liquidity from it to lend it to those in need on the periphery: central bank liquidity is useless unless primary dealers have balance sheet to pass it on, and that they’ve been passing it on since September does not mean they will at year-end.

Bill purchases are also ill conceived because banks and dealers don’t own any bills and so don’t have anything to sell to the Fed to boost their excess reserves ahead of year-end. In our view, the notion that bill purchases will force money funds down the yield curve to buy short coupons from primary dealers who would then pay off their repos with banks so that banks build up some excess reserves into year-end involves too many moving parts…

Which brings us to the first of the key observations made by Pozsar: since the Fed’s repos and T-Bill monetizations have done virtually nothing to boost prevailing reserve levels on a sustained basis, “year-end balance sheet constrains will preclude primary dealers from bidding for reserves from the Fed through the repo facility or through repos from money funds. The slope of money market curves suggest that excess reserves won’t build up at banks, and so U.S. banks will not be able to fill the market making vacuum left by foreign banks.”

In other words, the already thin liquidity at year end (which as a reminder, last December 31 sent repo rates soaring even though excess reserves were about $100 billion more than they are now) could get far worse as a result of the Fed’s inability to properly address the reserves (cash) shortage plaguing banks.

There is another reason why year-end liquidity is likely to get far worse, and it has to do with bank year-end G-SIB surcharges imposed by regulators on US banks on the last day of the quarter and year. As we discussed two weeks ago, and as Pozsar explains, “running low on excess reserves is only one factor that determines how bad the vacuum

in market making can get around year-end turns. G-SIB scores are the other, as they determine what banks can do with whatever excess reserves they have at year-end: lend them through repos, spend them on Treasuries, or lend them through FX swaps, – in that specific order as repos are less punitive for banks’ G-SIB score than FX swaps.”

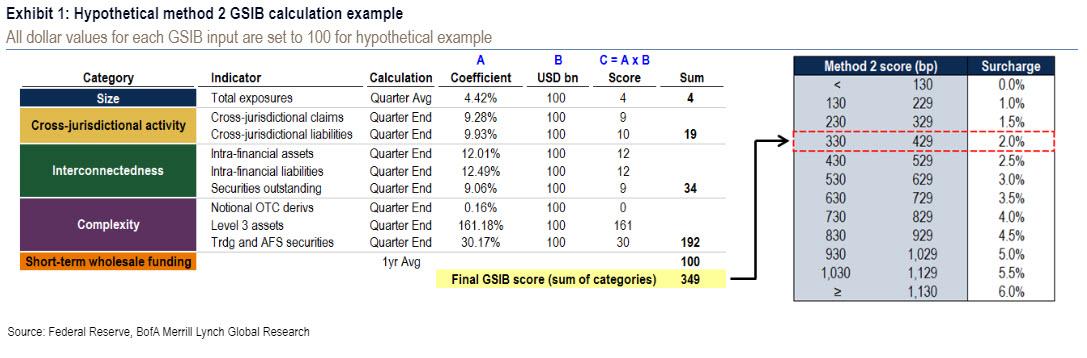

We previously provided a simple schematic of how bank G-SIB scores are calculated in the following chart…

… but the bottom line is the following: banks seek as low as GSIB score as possible at year end to minimize their period end surcharge:

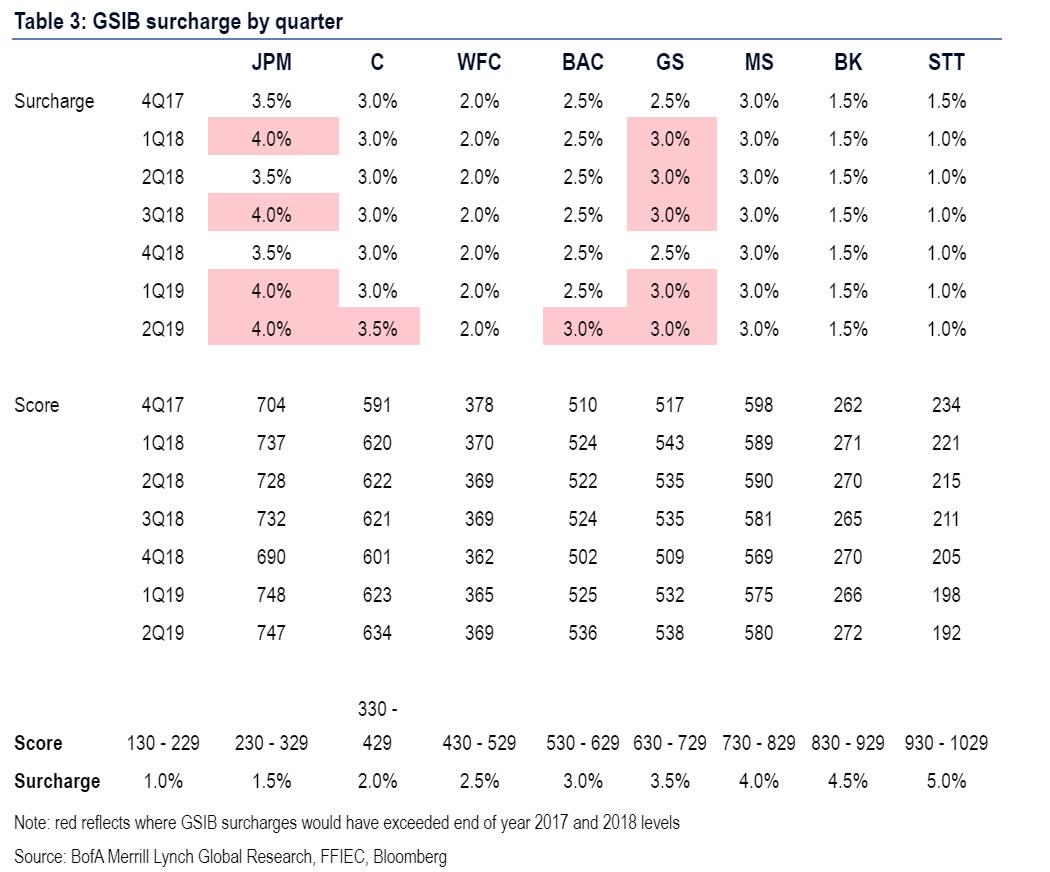

As Pozsar further notes, “U.S. banks are particularly sensitive to their G-SIB scores this year, as they all moved up to a higher surcharge bucket due to bigger Treasury holdings and a heavier repo footprint: every U.S. bank except Morgan Stanley has an incentive to shrink its score into year-end.“

It is here that a unique paradox emerges: the highest stock prices rise, the higher the implied score (a negative). Some more observations from the repo guru:

G-SIB scores are a moving target as they are influenced by markets. The themes pushing G-SIB scores in the wrong direction this year are the equity market rally and the flat curve:

(1) the rally in equities is inflating scores through G-SIBs’ market capitalization and the value of equities G-SIBs hold as trading assets or available for sale securities;

(2) the flat yield curve is inflating scores through G-SIBs’ bloated Treasury portfolios, which, given auction supply and the equities rally, may grow further into year-end.

While G-SIBs can’t do a thing about the equity market, and, as the largest primary dealers, they also can’t not take down more Treasuries at auctions if there are insufficient bids; but they can do two things to offset some of the factors that are pushing their scores up:

- collateral upgrades where they repo equities out to raise some excess reserves, or repo or outright sell some of their Treasuries to raise some excess reserves.

- clamping down on market making in the FX swap or sponsored repo markets whereby they’d add to the vacuum in market making triggered by foreign banks

Which brings us to the other key year-end dynamic: when G-SIB scores are too high and banks need to reduce them, they do so by swapping assets for excess reserves. In other words, when banks hold lots of excess reserves their G-SIB scores are relatively low and they have room to lend their excess reserves through repos and FX swaps, and conversely, when banks are low on excess reserves their G-SIB scores are high and that may force them to clamp down on market making.

Well, as we know from the discussion in the first part above, bank excess reserves have collapsed and as a result G-SIB scores are high, “and banks are lowering their scores by swapping assets for reserves to scrape together some excess reserves ahead of the year-end turn – and those scraps are all U.S. banks will have to lend into the market making vacuum left by foreign banks around year-end.”

In the best case scenario envisioned by Pozsar, bank will lend mostly via repos and not FX swaps given their G-SIB scores. “But these flows will be scraps of excess reserves, not bursts.”

As for the worst case scenario, it is one where “collateral upgrades aren’t sufficient and U.S. banks stop making markets in FX swaps and so exacerbate the vacuum triggered by foreign banks.”

Which brings us to the first of Pozsar’s ominous conclusion: “We are on track to realize the worst case scenario, and the market doesn’t price for that.”

Here, Pozsar offers a brief detour offering some practical observations as we enter the year-end period, in which he notes that “according to our conversations with market participants, U.S. G-SIBs rely heavily on Canadian pensions for equity upgrades to accumulate some excess reserves for the turn. Furthermore, some large U.S. banks are selling Treasuries to lower their G-SIB scores and scrape together some excess reserves to harvest higher repo rates over year-end.”

Finally, and most shockingly, the Credit Suisse strategist writes that “at least one large U.S. bank appears to be pricing some of its FX swaps trades such that it misses those trades – a polite way of clamping down market making activities.”

Here some readers may have a “lightbulb” moment because what Pozsar just described is that “at least one large US bank” appears to be gearing for a collapse in the FX swap market, with a very specific intention: to force a market crisis in the coming days and force the Fed to launch full blown QE 4, not just a monetization of T-Bills.

More on that momentarily.

But first, some more observations from Pozsar on how a year-end crisis may play out: “if markets won’t let G-SIBs reduce their scores, G-SIBs will retort to scale back market making, like the one U.S. bank that’s already pricing FX swap trades to miss them. We do not see the pressure from this in FX swap markets yet as foreign banks still have balance sheet to pick up the slack, but pressures will come as we get closer to year-end.”

Pozsar’s point is that the realized year-end turn in FX swap markets “will be worse than what is priced by the market regardless of whether we end up in the best case or worst case scenario.”

This literally means that no matter what the market does from now until year end, there is simply not enough cash and/or liquidity to allow the plumbing of the market to cross into 2020 without a crisis, or as Pozsar puts it, “in our view, the FX swap market is expecting too much similarity between the current year-end turn to last year’s turn. That’s a mistake as last year’s dynamics were different” for the following reasons:

- large U.S. banks still had excess reserves to lend, but this year they do not; and

- they got a G-SIB relief from a 20% fall in equities, but this year end they do not

One other key difference from the brief meltup in repo rates last year end: back then, lower G-SIB scores allowed large U.S. banks to spend their hoards of excess reserves on more complex trades like FX swaps, and the year-end turn went down as a non-event – in FX swaps, but not repos. Recall that repo printed at 6.5% on December 31st spot.

This year, Zoltan warns, may be the opposite, as higher G-SIB scores will favor repos over FX swaps when deploying excess reserves, but while FX swaps will be a disaster, repos may still print as bad as last year-end. As for FX swaps, well we’ll leave Pozsar to explain what may happen there:

“FX swaps could end up as the orphaned asset class without an obvious backstop, and that may force banks in some parts of the world to the edge of the proverbial abyss“

As a reminder, this dire warning comes from the man who probably knows the nuances of the US repo market better than anyone else in the world.

But wait, there’s more.

Recall that in its BIS’s recent take on the fireworks in the repo market, the central banks’ central bank pointed the finger at massively levered hedge funds engaging in Treasury relative value trades (think of these as a modern twist on the LTCM trade) as the catalyst for the Sept 16 repo explosion,

“High demand for secured (repo) funding from non-financial institutions, such as hedge funds heavily engaged in leveraging up relative value trades,” was a key factor behind the chaos, said Claudio Borio, head of the monetary and economic department at the BIS.

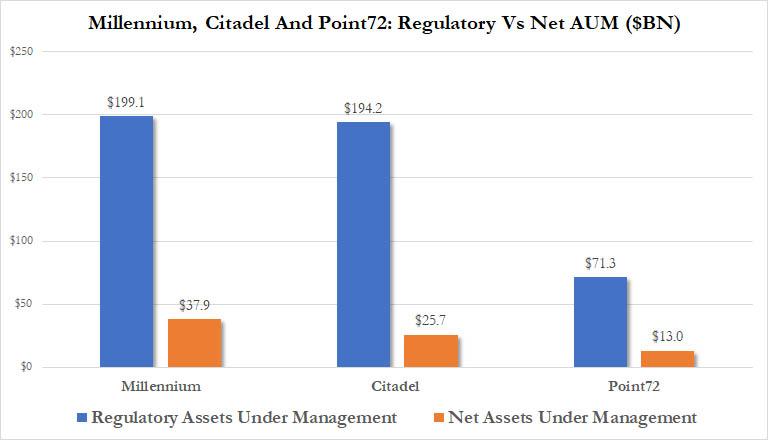

The BIS’s finding was novel, and surprising, as it highlighted the “growing clout of hedge funds in the repo market” echoing notes something we pointed out one year ago: hedge funds such as Millennium, Citadel and Point 72 are not only active in the repo market, they are also the most heavily leveraged multi-strat funds in the world, taking something like $20-$30 billion and levering it up to $200 billion. They achieve said leverage using repo.

And, as we further discussed, the hedge fund strategy in question involves buying US Treasuries while selling equivalent derivatives contracts, such as interest rate futures, and pocketing the arb, or difference in price between the two. While on its own this trade is not very profitable, given the close relationship in price between the two sides of the trade. But as LTCM knows too well, that’s what leverage is for. Lots and lots and lots of leverage.

We took this detour into how repo affects the hedge fund world, because Pozsar had a rather gloomy prediction about the fate of hedge funds should his dismal forecast materialize. As he writes, “the relative value (RV) hedge fund community is certain that they will have balance sheet to fund their bond basis trades at reasonable rates over the year-end turn. Why?

“Because we have locked up forward settling sponsored repos with dealers over the turn, and market making in sponsored repos is less likely to be scaled back than in FX swaps.”

Well, not so fast:

Forward settling sponsored repos are meant to substitute for the balance sheet that the RV hedge funds will lose from foreign banks around year-end, but their risk is that RV hedge funds don’t know the rate at which they’ll get balance sheet at year-end – forward settling sponsored repos only lock in balance sheet capacity, but not the rate and with all due respect, RV funds are ignoring the incentives of repo dealers.

Fast forwarding to the punchline, the problem is that without having intelligence about the balance between forward settling sponsored repos and banks’ progress to scrape together excess reserves to fund those forward repos, Pozsar warns that relative value funds “don’t know where the rate on their forward settling sponsored repos will print. And given that there are no signs of excess reserves accumulating into year-end, it is likely that the RV community will be taxed excessively to get over the year-end turn.“

The bolded means that massively levered hedge funds may be in for a shock in the coming days, as bank sponsors are woefully low on the reserves that the hedge funds need to perpetuate their RV trades (and leverage) into the new year.

This, too, is a problem. Here’s why:

As the excess reserves missing from bank portfolios will be filled by a small cadre of primary dealers that do not have balance sheet constraints and they’ll fill the hole and keep a lid on repo rates. Sure, let’s assume for a moment that those primary dealers that are not subject to Basel III – Amherst Pierpont Securities LLC, Cantor Fitzgerald & Co. and Jefferies LLC – and three Canadian dealers whose year-end was on October 31st – the Bank of Nova Scotia, BMO Capital Markets Corp. and TD Securities (USA) LLC – will save the day by borrowing enough from the Fed to bridge your needs in repo markets.”

Pozsar’s snarky conclusion to this? “Maybe, maybe not.” We’ll take the latter.

Putting all of the above together, and for those unfamiliar with the nuances of the repo market this summary may be a critical catch up, the risk to the “benign and optimistic view” currently prevailing among market participants, is mostly as related to the FX swap market: given that i) excess reserves are gone and ii) the G-SIB scores bind, “the FX swap market, unlike last year-end, may end up without a lender of next-to-last resort, and so it will likely trade at implied rates far worse than anything that we’ve seen in recent year-end turns.”

If that will indeed be the case, Pozsar envisions a last few weeks of the years in which the handful of Canadian dealers you expect to lend to you to fund your bond basis trades, will instead lend in the FX swap market instead “and you’ll end up short… and you may end up as a forced seller of Treasuries.”

What is even more stunning is that banks themselves may have an incentive to cause this lock up in the FX swaps market: Pozsar’s overarching point is that “a dealer is a hedge fund’s enabler, not its friend, and dealers that co-exist with large bank operating subsidiaries have an incentive to introduce imbalances the repo market to boost the value of their banks’ excess reserves, and dealers that have the balance sheet to take liquidity from the Fed’s repo operations will not necessarily do repos with RV hedge funds if FX swaps offer a much better value.“

* * *

With us so far? Good, because we are finally getting to the punchline.

In this dystopian world described by Pozsar, in which banks have too much “collateral” (Treasuriess) on their books, and not enough “reserves” (cash), where big commercial banks are unable to lend out to the rest of the banking system as they themselves don’t have enough reserves, and where there will be an added pressure to boost reserves in the last days before Dec 31, Pozsar’s big picture conclusion is that “the safe asset – U.S. Treasuries – is being funded o/n and therefore it depends on balance sheet to be held and printed. Balance sheet for the safe asset isn’t guaranteed around year-end and if balance sheet won’t be there, the safe asset will go on sale.”

Translated: “Treasury yields will spike”, Pozsar warns, identifying the trigger of forced sales of Treasuries around year-end as the FX swap market. It gets worse, because the selloff that is triggered by a freeze in the FX swap market will promptly lead to a crash in the bonds market, and spread from there, or as Pozsar puts it, “these funding market stresses will likely pull away capital and hence balance sheet from equity long-short strategies which could spill over into a broader equity selloff… during a Treasury selloff – that’s not the right kind of risk parity Christmas.“

Which brings us to punchline #1: the dismal liquidity situation within the US commercial bank sector is so dire, that the shortage of reserves will start a cascade of liquidations beginning in the FX swap market, progressing to Treasurys, and culminating in stocks… and a full-blown market crash.

When these pressures will show up and how long they will last is the last big question asked by Pozsar and as he answers,

“here it’s hard to have a definitive answer: it depends. It depends on how equities do, which depends on the trade deal and other random tweets. It depends on how auctions go, which depends on the equity market and the curve slope relative to actual funding costs.”

We should note here that the next major tax remittance to the Treasury is on Dec 16. It was the same Sept 16 tax payment that according to many triggered the repo carnage by draining tens of billions in reserves from the banking system. Will lightning strike twice, and on the same day no less than the day the US-China trade deal is expected to be signed?

One especially ironic development is that higher stock prices in the coming weeks will only make the matter worse! “If the equity market rallies and auctions go poorly, G-SIB scores will keep going higher and the risk that funding market pressures from managing G-SIB scores will show up starting the last two weeks of the year and will last longer than just the spot turn are rising.“

Said otherwise, the dire warning from arguably the top expert on the repo market is that the adverse cascade will begin in the last two weeks of the year meaning that… traders have about a few days to take preventative measures.

That said, there is one potential “out” – the Fed steps in.

Just in case anyone still has a rosy outlook on what the next three weeks may bring, Pozsar repeats his devastating conclusion: “Year-end in the FX swap market is thus shaping up to be the worst in recent memory, and the markets are not pricing any of this. Prices don’t seem to discount the facts that excess reserves are gone and the Fed’s operations still have not added any, and that G-SIB scores are binding and risk large U.S. banks clamping down on market making.”

Worse, another prevailing consensus idea is that the Fed will not cut one more time in December “to deliver slope in the money market curve so that reserves from bill purchases flow up to banks… or that the Fed will actively encourage the use of FX swap lines around year-end to get around G-SIB bottlenecks; or that the Fed will start buying coupons from dealers to inject excess reserves in a balance sheet neutral and G-SIB score-reducing manner.”

What Pozsar is stating in not so many words, is that as has happened on every other previous occasion, the Fed will have no choice but to intervene to reverse the coming crash, only this time with its ammo severely limited, there is just one thing that Fed can do, or as Pozsar says, “something will have to give and the turn has to get very bad before something gives.”

But will things get “very bad”? Well, if Pozsar is right and the Fed loses control over the overnight rate complex, yes, they will, and as we tweeted some practical advice yesterday…

… The question then is what will the Fed do. Here is Pozsar’s answer: “If we are right and the Fed loses control over the o/n rates complex going into year-end – not just around the spot turn but the weeks leading up to it – what else can the Fed do?”

- encourage foreign central banks to use of the FX swap lines;

- start QE4 by switching from buying bills to buying coupons;

Of the two options, Pozsar believes #2, the Fed launching QE4 (in the next fed days), would be the proper decision:

QE4 would help through the backdoor: by reversing the mistake of balance sheet taper. QE4 would mean buying back from dealers and banks the Treasuries they were forced to buy during balance sheet taper and giving back the reserves they gave up in the process.

QE4 would re-liquefy HQLA portfolios by trading Treasuries for excess reserves: the excess reserves that were always needed to get through to year-ends seamlessly, and which the system’s liquidity profile and U.S. banks G-SIB scores need desperately.

QE4 would re-fill the “Bakken Shale” in an instant: as primary dealers stuck with Treasuries would pay off their repos with J.P Morgan, and that would bring us back to the natural state of the token system, that is, a state, where the distribution of excess reserves is uneven once again, and where J.P. Morgan is the system’s lender of next-to-last resort once again.

That said, as Pozsar concedes in his conclusion “QE4 – as much as it makes sense – won’t happen unless the Fed’s hands are forced.” By which he means there has to be a market crash for the Fed to do the one thing that can alleviate the banks’ terminal reserve problem.

The Credit Suisse strategist admits as much:

“not responding to potential stresses in the FX swap market with the swap lines, may be what forces the Fed’s hands. If it will take the swap lines to help RV hedge funds to roll their positions without the risk of fire sales, not encouraging their use preemptively can lead to fire sales where QE4 goes live as a clean-up “operation” with the Fed buying what the RV funds are forced to sell – and what they could have bought from dealers under normal circumstances as dealers have been politely asking the Fed since September, just like they were asking for a repo facility before that – and we know how that ended…”

In conclusion all we can say here is that 11 years ago, on September 5, 2008, ten days before Lehman filed, there were massive marketwide repo problems (recall the repo market froze in Sept 2008 and only a multi-trillion bailout by the world’s central banks prevented civilization collapse) and almost nobody understood them… with one exception: Citi’s Matt King did and he laid out all the problems in his iconic Sept 5, 2008, piece “Are the Brokers Broken” in which he predicted the collapse of Lehman. Ten days later he was right. Will Zoltan Pozsar be this generation’s Matt King?

Pozsar’s full “Countdown To QE4″ can be read here.

RTD 1oz. Round

RTD 5oz. Round

0 Comments